Introduction

The most important component of the time-series database is a compression engine because it defines the trade-offs, and the trade-offs are shaping the architecture of the entire system.

General purpose compression libraries (lz4, zlib) are not the best fit for the job. All these libraries are designed with large data volumes in mind. They require a large amount of memory per data stream to maintain a sliding window of previously seen samples. The larger the context size the better compression ratio gets. As result, these compression algorithms usually achieve very good compression ratio on time-series data at the expense of memory use, for example, lz4 requires about 12KB of memory per context (stream).

Akumuli uses B+tree data structure to store data on disk. This data structure is built from 4KB blocks. Each block should have it’s own compression context (otherwise it wouldn’t be possible to read and decompress individual data blocks). With most general purpose libraries this context gets larger than the block itself. Of cause, only one compression context needed per tree most of the time. But the problem is that many trees should be maintained in parallel (Akumuli maintains B+tree instance per time-series) and for each tree, individual compression context is required. E.g. if we’re dealing with 100’000 time-series we’ll need about 1GB of memory only for compression contexts.

This is the rationale for the specialized compression algorithm. This algorithm should have tiny memory footprint in the first place. It should deal with both timestamps and values. General purpose encoders can process data of any sort but in the specialized algorithm different encoders should be used for timestamps and values. In this small series, I’ll try to describe how this specialized algorithm is implemented in Akumuli. This article is about timestamps and the next one will be about floating point values.

Akumuli store timestamps with nanosecond precision as 64-bit integers. Most data sources don’t use all this precision and lowest bits are usually zeroed, in this case, series of timestamps can look like this (with 5s step):

...

0x58250a0000000000,

0x58250a0500000000,

0x58250a0a00000000,

0x58250a0f00000000,

...

Note that first 4 bytes of each timestamp contains only zeroes. If we use Delta encoding on this data, the result will be this:

...

0x500000000,

0x500000000,

0x500000000,

0x500000000,

...

This values can be compressed using variable-width encoding (e.g. LEB128 or static Huffman tree, these encodings can represent small values using just a handful of bytes so we will be able to store Delta-coded values using less memory). But the values is relatively large and we can’t benefit from variable-width encoding much, e.g. value 0x500000000 can be represented by the LEB128 encoding using five bytes (less than 50% savings). To improve further we can use Delta-RLE or Delta-Delta encoding followed by variable-width encoding. With the dataset shown above, both approaches will work great. But in the real world, we should deal with non-periodic data sources and high-precision timestamps with noise. For non-periodic data sources, Delta-Delta encoding will work better. For periodic data sources, Delta-RLE will work much better (series of timestamps will be collapsed into a dozen of bytes).

Series of high precision timestamps that have some noise in low bits can look like this:

0x58250a000000fa00,

0x58250a050001b500,

0x58250a0a00013500,

0x58250a0f00001c00,

...

Here the interval between timestamps is not exactly 5 seconds because of noise in the lowest bits (in microsecond domain). This dataset will totally defeat the Delta-RLE encoding but Delta-Delta will work just as usual.

It turns out that we may want to use different encodings in different situations but most of the time Delta-Delta is the best option. It’s tempting to use Delta-Delta always but Akumuli implements a unique adaptive approach that works better. To describe it I need to start from the underlying variable-width encoding.

VByte encoding

Akumuli uses modified version of the LEB128 encoding. The original LEB128 uses low 7 bits of each byte to store a portion of data and high bit is used as a continuation flag. If this flag is set to zero then this byte is the last one otherwise, the next byte should be decoded. This encoding is used by Protobuf (https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/docs/encoding#varints) and many other systems.

This algorithm suffers from poor performance. Encoding and decoding processes require a lot of bit-level manipulations. We need to extract 7 bits from each word (by masking and shifting) and then we should check the high bit (shown in yellow on the diagram) The result of this operation can’t be predicted by the branch predictor well enough.

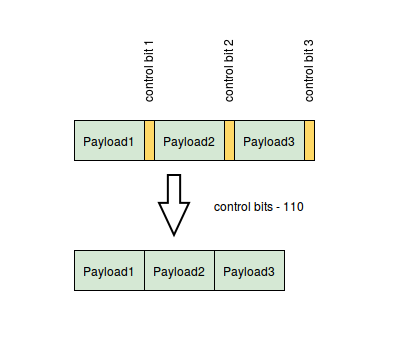

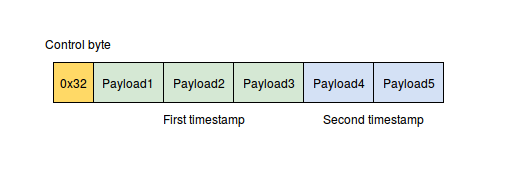

Akumuli uses a different approach. Each 8-byte timestamp is stored in a series of bytes (0-8). Each byte encodes 8 bits of the timestamp and there is a separate 4-bit flag that contains the number of bytes being used (in original LEB128 encoding this number is actually stored in high bits of every byte). Timestamps are encoded in pairs and 4-bit flags are combined into full bytes to save space. This approach is close to Group Variant Encoding used by Google (http://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/ru//people/jeff/WSDM09-keynote.pdf).

The decoding algorithm is straightforward, we have a control byte followed by a dozen of bytes with data. Decoder reads control byte and extracts first four-bit number. This number encodes a number of bytes used to store first value. Then decoder extracts the second four-bit number from control word and reads the second value. If both values are zeroes then no extra payload will be stored, only the control byte. This is a very simple and branchless algorithm.

Encoder algorithm is very simple as well. First, it counts a number of leading zeroes using the __builtin_clzl function. This function returns a number of leading zero bits in the double word. This number is used to determine the number of bytes needed to store the timestamp. This number is recorded in control byte and then meaningful part of the timestamp is stored as is (without shifting or masking, just a single memcpy).

You may already notice that each four-bit number can contain a value in the [0, 8] range because timestamps are 8-bytes long. But using four bits we can store a value in the [0, 15] range thus almost half of the range is left unused!

Now let’s take a look at Delta-Delta encoding once again. Delta-encoding is applied first, then Akumuli divides all delta values into series of fixed-sized chunks. After that, the algorithm searches for the smallest delta in each chunk and subtracts this delta from every value in that chunk. As result, from each chunk encoder produces N+1 values - smallest delta and the list of N positive delta-delta values. Example (N=4):

0x58250a000000fa00,

0x58250a050001b500,

0x58250a0a00013500,

0x58250a0f00001c00

The result will look like this:

0x500001c00, # smallest delta value

0xde00,

0x19900,

0x11900,

0x0

To store original chunk using VByte encoding we will need 34 bytes (2 control bytes + four 64-bit values). To store Delta-Delta encoded chunk we will need only 16 bytes (5 + 2 + 3 + 3 + 0 bytes for payload and 3 control bytes). Note that the chunk is small (only 4 elements). With larger chunks, compression will get much better.

But what about equally spaced timestamps? Let’s look at the example:

0x58250a0000000000,

0x58250a0500000000,

0x58250a0a00000000,

0x58250a0f00000000,

After Delta-Delta encoding step this series will look like this:

0x500000000,

0x0,

0x0,

0x0,

0x0,

We can see that smallest delta is followed by the series of zeroes. To store this using VByte encoding we will need only 8 bytes (5 bytes to store the min-delta + 3 control bytes). This is quite good but what if the chunk will get larger? E.g. if N = 16 we will need 8 control bytes, 16 bytes if N = 32 and so on.

This isn’t a bad result but compression can be improved further. Akumuli uses a simple trick here. If encoder encounters this pattern (min-delta followed by N zeroes) it writes min-delta and then it writes single 0xFF control byte. This control byte can’t be produced during normal operation (because timestamps are 8 bytes long), and when decoder sees this value it generates N zeroes. Using this trick, series from the last example can be stored using 7 bytes but this value will be the same for larger chunks.

This algorithm is branchless and very fast (there are some branches actually, but that branches can be optimized by the compiler or easily predicted by the processor e.g. for-loop condition). On my laptop (Dell XPS with ULV Intel Core i5 processor) it can compress about 40 million datapoints/second.