NOTE: this article is out of date. Akumuli doesn’t use this component anymore.

Akumuli is a time-series database input for which is supposed to be generated on different machines in the network. Each computer has its own time source that can be used to generate data. Clocks on different machines can be skewed and because of this time-series database input can be slightly unordered. Akumuli’s input is an almost sorted dataset. Because of this akumuli has a sequencer component. Sequencer is used to buffer and sort input on the fly. It is some sort of cache and sorting algorithm in one package. In this article I’ll try to describe how it works.

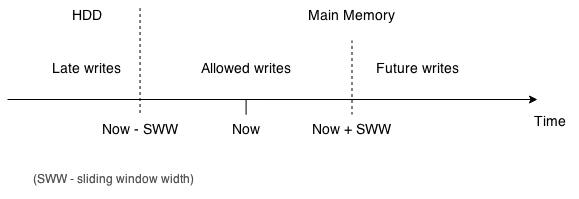

Akumuli has a notion of the sliding window. Each data element has a timestamp. If some data element’s timestamp doesn’t fit into the sliding window this data element is old and most likely was created by error. Akumuli only accepts data elements from not too far future and not too far past. Width of the sliding window is defined in configuration. Sequencer stores data that fits the sliding window. When data element gets too old and leaves sliding window, sequencer writes it to the disk and removes it from main memory.

Sequencer should have some special properties.

- It should be possible to read data from sequencer.

- Readers shouldn’t slow down writers, sequencer should be parallel.

- Sequencer should be able to tolerate high insert rates.

- Input is almost sorted. Because of that it will be good if sorting algorithm will be adaptive.

- Sorting algorithm should be online.

My first try was a google’s B-tree implementation. It’s pretty cool because it has biased insertion - special case when keys are inserted almost in order and rebalancing is not needed. It is possible to insert data into B-tree really fast if input is only slightly reordered. But at the end I’ve moved away from this implementation because it requires excessive locking.

My second and successful try was patience sort. It is described in great detail in this paper. Patience sort is an adaptive sorting algorithm. When input is already sorted it will be just one pass over the array in linear time. When input is slightly unordered it will produce several sorted runs but remains quite fast.

Input:

[0, 1, 4, 2, 3, 7, 6, 5, 8, 9]

Sorted runs:

[0, 1, 4, 7, 8, 9]

[2, 3, 6]

[5]

The worst case (that is very unlikely with time-series) is reverse order of the elements in the input stream. In this case patience sort will turn into merge sort (very inefficient one). At the end this sorted runs can be merged using simple N-way merge, producing single sorted sequence. And it is possible to perform binary search on this sorted runs and merge results in the same way. Very handy.

This sorting algorithm can be turned into online form using simple time-based partitioning. All the data elements with timestamps that fit into the same sliding window go into the same bin. When bin became old and immutable (because late writes are prohibited) it should be merged and written back to the disk as one chunk. So in fact, sequencer performs a series of patience sort rounds.

The most tricky part is transition between writable in memory state and immutable disk baked state. Reader can read data from the disk before last bin is merged to disk and the read in memory data just after the latest bin was merged. In this case client will see the gap between in-memory and on-disk data. This should be solved using proper synchronization.

Synchronization

Imagine that we have a bucket of sorted runs (simple sorted arrays of elements). Each write to the database updates one of the sorted runs in the bucket or creates a new one. At the same time it is possible that another thread is reading one of the runs.

[0, 1, 4, 7, 8, 9] <-- New write goes here

[2, 3, 6] <-- Somebody reads this

[5]

Akumuli solves this using array of read-write mutexes. Each reader before reading data from run number M calculates index the of the read-write mutex in the array - index = M % array length. After getting read-lock thread can start reading. Writer does the same thing, it calculates index of the mutex, gets write-lock and after that it can update the sorted run.

But this is not the end. Consider the following situation: reader starts to read data from sequencer, when it starts reading merge procedure is initated by writer-thread (last chunk is merged to HDD), while reader doesn’t still finish - the number of chunks in the sequencer is changed (one was gone). One possible solution is to use synchronization between readers and writer, when writer wants to merge chunk it should asquire exclusive lock. The problem is that using lock we can create write starvation, if many readers are active at the same time writer could be blocked for arbitrary time, affecting write performance. This is a problem.

Optimistic concurrency control

This issue is solved in akumuli using optimistic locking. Sequencer has an atomic built in counter called sequence_number. Sequence number is set to zero initially. It is incremented every time merge is initiated and completed so if sequence_counter is odd then merge is in progress and if it is even merge is completed. Reader-thread can check that sequence_counter is odd and wait for some time and retry if this is the case. But what if merge is started after reader-thread already did this check? To solve this reader-thread simply remembers sequence_number value and compares it with sequence_number after read was completed. If merge has started they wont match. In pseudocode this algorithm loocks like this:

fn reader() {

seq_id = sequence_number

if (seq_id % 2 != 0) {

return BUSY

}

serch_results = read_sequencer_data()

if (seq_id != sequence_number) {

return BUSY

} else {

return search_results

}

}

This is an oversimplification of cause but it can show the idea. If reader gets the BUSY error it just retries. Code of the sequencer can be found here and here. Method Sequencer::search contains actual synchronization code, merge_and_compress and merge methods is an another side of the coin.

Akumuli have some performance tests for this subsystem:

- parallel_test pushes a lot of messages in one thread and reads everything back in another thread. It shows promising results - write reate is slighly affected by reader thread but not match. Note that read and write jobs are quite heavy.

- sequencer_test pushes a lot of messages to the sequencer without writing anything to disk. This code was used to profile sequencer and find bottlenecks.